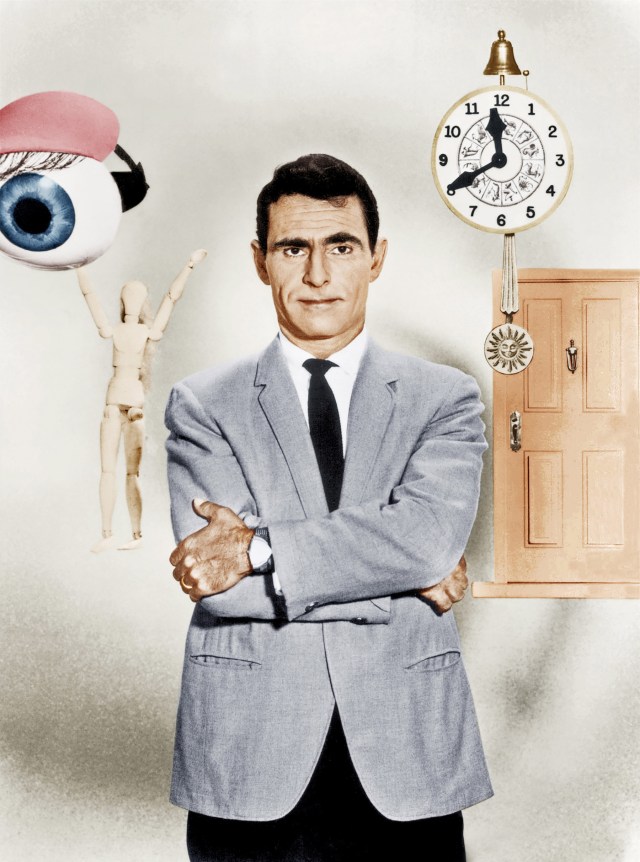

We all have an image of the late Rod Serling in mind, mostly instilled by his Classic TV series The Twilight Zone, which made its debut over 60 years ago, or by the fact that he wrote the early drafts of the screenplay for 1968’s Planet of the Apes. That image, of course, is of Rod standing before us, arms crossed in front of him, quite seriously filling us in on the latest denizen of that world beyond imagination before ending it all with a mind-blowing twist. But if you were to talk to his daughter, Anne Serling, a very different portrait would be painted.

“He was brilliantly funny,” she says in an exclusive interview, “just playful, silly and fun to be with. He’d do things like disappear into the other room and come back with a lampshade on his head. He was a practical joker and loved anything for a laugh. I can remember him frequently telling a joke and getting hysterical in the middle of it, going to slap his knee, missing it and unable to finish the joke … I guess it’s the total opposite of what you’d imagine.”

To put it mildly.

The Twilight Zone originally aired for five seasons between 1959 and 1964 and remains a powerful part of pop culture all these years later. It’s been the subject of a number of TV series remakes from 1985 to 1989, 2002 to 2003 and, most recently, beginning in 2019 on the CBS All Access streaming service and produced by Jordan Peele. In between, there was the 1983 feature film produced by Steven Spielberg, stage adaptations of episodes beginning in 1996, a 2001 radio show featuring adaptations of the TV scripts, and the 1994 to 2017 Disney theme park attraction, The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror. On top of that, there are annual marathons of the show on different TV channels. Needless to say, TZ isn’t going anywhere.

While there have been a number of biographies of Rod (who died in 1975 at the age of 50) and the series published over the years, none have taken the personal approach as Anne’s As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Serling, which was, in one way, written in response to all those other books. “The depiction of my dad,” she explains, “as this dark, tortured soul, but that’s not who he was.”

The Twilight Zone celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2019 and it remains an important part of pop culture. What’s your feeling about that?

No one would be more surprised than my father that we’re still talking about The Twilight Zone and talking about him all these decades later. I’m not the first person to say this, but it’s still in our vernacular because his issues that he dealt with are still so relevant and prevalent. He dealt with the human condition and things, sadly, don’t change. We’re still dealing with prejudice and mob mentality and the resurgence of nationalism; he’d be deeply, deeply saddened by all of this.

Did he feel The Twilight Zone would be very much of its time and not transcend its era the way it has?

I think he had a deep understanding of who we are and probably felt that things weren’t changing fast enough, but he also felt that it was quite important to talk about these issues and get them out there. He was quoted once as saying it’s a writer’s job to manage the public’s conscience and he was so censored that he launched into The Twilight Zone to get these messages out. An alien could say what a Republican or a Democrat couldn’t, so a lot of this just slipped under the radar and he was able to talk about all these important things.

Makes you wonder if executives were just dimwitted or felt it was safe because the stories were couched in allegories.

I don’t have an answer for that, though I’m sure there were some with a good conscience. I do have to say, he would have been honored and so grateful for the way it’s lived on. There’s actually an educational program in Binghamton called “The Fifth Dimension,” where all the fifth graders watch The Twilight Zone and learn about all these issues: mob mentality, scapegoating, prejudice, hatred. All of that, and they really get it. It’s amazing to me that these are fifth graders. In fact, one of the teachers told a story about how she showed the episode “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” and she asked the class who the monsters were. The whole class stood up and said, “We’re the monsters on Maple Street. They just get it.”

Just as amazing is that kids will pay attention to a show in black and white, which isn’t the norm these days.

It’s not that it’s just black and white, but things today move so fast and everything is so high tech that there isn’t a moment to stop. The Twilight Zone was a low budget show and much of it was dependent on the direction, the filming, and all that. I think that’s part of what makes it remain so powerful, but then I’m not 20.

What was his appraisal of the human condition?

Basically he thought that there was hope for people and he deeply cared. Despite everything that was happening back then, he still felt that we’d eventually get it together. That there were enough good people and bright people, and that this kind of adversity would end. We didn’t have a lot of discussions about that, but I remember my dad talking about prejudice a great deal and how it incensed him. He said it’s the greatest evil of our time. It’s a good thing that his own first experience with prejudice was when he was in high school and was blackballed from a Jewish fraternity for dating a non-Jewish girl. It’s interesting that it came from his own people.

Which of course would lead him to write stories that were so powerful on so many levels.

He hadn’t set out to be a writer; he was going to teach physical education to kids because he liked working with kids, but as he said, the war [World War II] put an end to that. He was quite traumatized and broken after the war and his father died while he was overseas as well, so there was a lot of unresolved grief. When he came back he went to Antioch on the GI bill and he said he went there because his brother went there, but like with so many vets, there’s PTSD — which wasn’t even a term back then. It was shell shock. But he finally changed his major to language and literature, because he said he had to get it all out of his gut.

A lot of which is dealt with in your book.

It’s really interesting to me that when I was writing my book, one of the most difficult and painful parts of it was when I read the letters that he wrote to his parents when he was in training camp. He sounds just like a kid at summer camp writing home for chocolate and gum. And it really broke my heart, because my son was the same age at the time as I was writing the chapters, and I just think about how young these guys are that we sent to these horrific wars and how deeply it affects them. I remember my dad having nightmares and in the morning I would ask him what happened and he would say that he dreamt the enemy was coming at him.

So it remained a part of him no matter how many years passed.

It was part of his everyday life. He was also wounded in the war, hit by shrapnel in his wrist and his knee. His knee would frequently go out when he was going down the stairs and he would fall, or it would spontaneously bleed. So he had not only all the emotional wounds, but the physical ones as well. But with the nightmares he was still having, that was one of the reasons I wrote my book. I was really tired of some people who described him having this dark and tortured soul, because that is not who my dad was. That’s not who he was to his family. That’s not who he was to his friends. He was brilliantly funny and even as a teenager I loved to hang out with him and so did my friends. Because he was fun. He was a practical joker, he was silly.

He had joy despite what he had been through.

His childhood, and he would have said this and did say this, was quite idyllic. He had that so deep in his heart. He captured that in a number of Twilight Zone scripts, especially “Walking Distance.” And there was a Night Gallery episode called “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar,” which dealt with the same theme. He taught a class in which he said he had a propensity to write about the path he had been on; that he had a deep yearning to be young again. In that “Walking Distance” episode, the father says to the older version of his son, “Is it really so bad where you’re from? Maybe you’ve just been looking behind. You need to look ahead.” I know that was the dialogue he wished that he could have had with his father. Just a beautiful show.

What was the experience of writing the book like?

It was actually a wonderful experience. I had tried to write a book after my dad died called In His Absence, but I was nowhere near resolving the grief that I was going through. I’m not unique to that, but I was pretty paralyzed after my father died and became agoraphobic. I just couldn’t pull it together, so it took me years to finally write this book. And there were three reasons I did: One, like my dad, I find writing cathartic and so it was a way to navigate through all that grief. Two, I wanted to know more about my dad’s professional life. And finally, the last reason, again, was to address what I talked about before about the depiction of my dad as this dark tortured soul. I did a reading before I was done writing the book at the Paley Center. A woman came up to me and told me that her father had a terminal illness and that he was going to die. She said after she heard me read, she knew she’d be OK and I was just blown away. Something I had said moved this woman and I couldn’t even speak; all I could do was hug her. You know, where we all are on this planet experiencing everything we are, a little kindness can go a long way. I felt for her, because it’s a long road.

So the memoir had an impact, which is wonderful.

And that’s one thing that’s really touched me, because since my memoir came out I hear from people all the time and they say things to me like they thought of my dad as their own father. Some of them came from very tumultuous childhoods and remember watching The Twilight Zone and just feeling so connected to him. I hear from others who say they became writers because of my father. It’s just really heartwarming to hear these lives that he touched. So many people. He had no idea, but, again, how grateful he’d be to know that. He was once asked what he would want on his gravestone and my father said that he left friends. When I was finally able, years after he died, to go his grave, somebody had left a message on a piece of masking tape attached to the flag on his grave that read, “He left friends.” It pretty much knocked me out.

How much of your dad would you say was in The Twilight Zone?

Certainly episodes that dealt with going back to the past, the episode about an SS officer going back to the concentration camps — this was his opportunity for a bit of emotional retribution, I guess.

It’s interesting that none of the reboots of The Twilight Zone connected. Obviously your dad is the missing ingredient.

Buck Houghton, a producer of the original Twilight Zone, said exactly what you did: The key element of Rod Serling is missing. Of course, I’m a little biased.

Did he have three daughters? Nan, Anne and Jody?

Dear Ms Anne Serling,

Please know your father would be very proud of you. And proud of the family he and your mother created. I wish so much I could have met your father. And I was going to go into writing, but I let something stop me. Reading this article about your reason for writing both books… You are very inspirational, thank you……. Sincerely, Irene